Cheering

My wife ran a half marathon in Pretoria a couple years back. (Actually, she accidentally only ran 10k, but that is another Africa story for another time.) Our son and I were among the crowds gathered in the big field at the finish line, where spectators set up awnings and chairs, made food, and settled into race day festivities. We picked a spot to wait, and as the first racers started coming in, we started whooping and clapping and hollering.

At this point, the other spectators, sitting on blankets or standing at their grills, turned and stared at us like we were crazy. As the exhausted runners continued past, desperate for the finish, my son and I were the only ones cheering. The runners themselves looked at us with huge smiles, gave high-fives, and through their heavy breathing, thanked us. The people around us continued to gawk. It went on and on like this. So many onlookers had come all this way for an early morning race, but it was clearly not the cultural norm to offer encouragement, even when the runners themselves kept responding so gratefully. We kept cheering.

This is one of the South African moments that I can’t shake, one of the symbolic pictures in my undertaking to know and love this country. On the one hand, there were so many people of all skin colors rising together to meet a challenge that day. On the other hand, while so many were struggling to achieve something great, no one was cheering for each other.

Let’s be honest: all you have to do is yell and clap. Cheering is fun. I can’t not cheer when someone is inspiring me and doing something amazing. Cheering isn’t hard. Something that is hard, however, is forgiveness. And I’ve slowly realized that perhaps this is what makes it difficult to cheer here.

In the long run, apartheid screwed everyone. Black and coloured people, obviously, for the generations of being treated as less than human. Without equal education or ownership over their own land or destiny, it continues to be a slow slow climb to live equitably in this now modern culture and country that they didn’t get much input into designing. I can’t even imagine this journey.

But white people walked away limping too. It is no small task to have all your expectations and opportunities turn on a dime. Life, as white South Africans knew it for generations, largely came out from under them. In the short time since Mandela, the government and police systems have become notoriously corrupt, and crime, including violent crime, is rampant. To provide equal opportunity for blacks now seeking better jobs, I hear it has become difficult to get hired as a professional if you are white. White South Africans who inherited land from their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents, are shamed because it was originally stolen from black people centuries ago. Who is the rightful owner of any of this anymore? This is no longer the country that the white people built either.

There’s nowhere to run from any of the unfairness on either side. South Africans of every race are not visitors like me, they have South African passports and this is their home. This is their story to navigate. These different groups, each nursing their own wounds, must forge a new country and a shared identity. So far, the best way I can describe my observation of the state of this nation is that there’s still messes to undo, new and old, not nearly enough opportunities for the number of people that need them, and in the meantime, people are not yet cheering for each other.

I don’t just mean at running events, of course. It is hundreds of tiny interactions, between people of all skin colors. To cheer for someone in the daily slog of life, to offer a smile or a gracious thought, is something that must be cultivated. You can’t genuinely cheer if you feel resentful. You have to imagine what he or she might have had to overcome to arrive in this moment. You have to rise out of your skin and be gratefully in awe of humanity, to the point of overflowing. You have to be proud of someone else’s success, because you have faith that everyone’s ability to thrive is intimately connected to yours. There is even a word for it here: Ubuntu. This word is a goal that none of us have mastered yet.

These growing pains are not easy. Everyone here seems to think they got the short end of the stick in this tale, and in some ways, everyone did. In this formative era of democracy, new laws and systems must go hand-in-hand with a change of heart, and not just for the white people. Everyone must find ways to approach connection without primarily feeling defensive and entitled. They must learn to trust, and earn that trust, which are two tall orders for absolutely everyone. Mandela worked to inspire them, but each must build some new pathways in their own hearts if they want to find a way to rise up together. And I’m pretty sure that together is the only way up from here.

Diepsloot, the township near our house

Us at the SA Constitutional Court

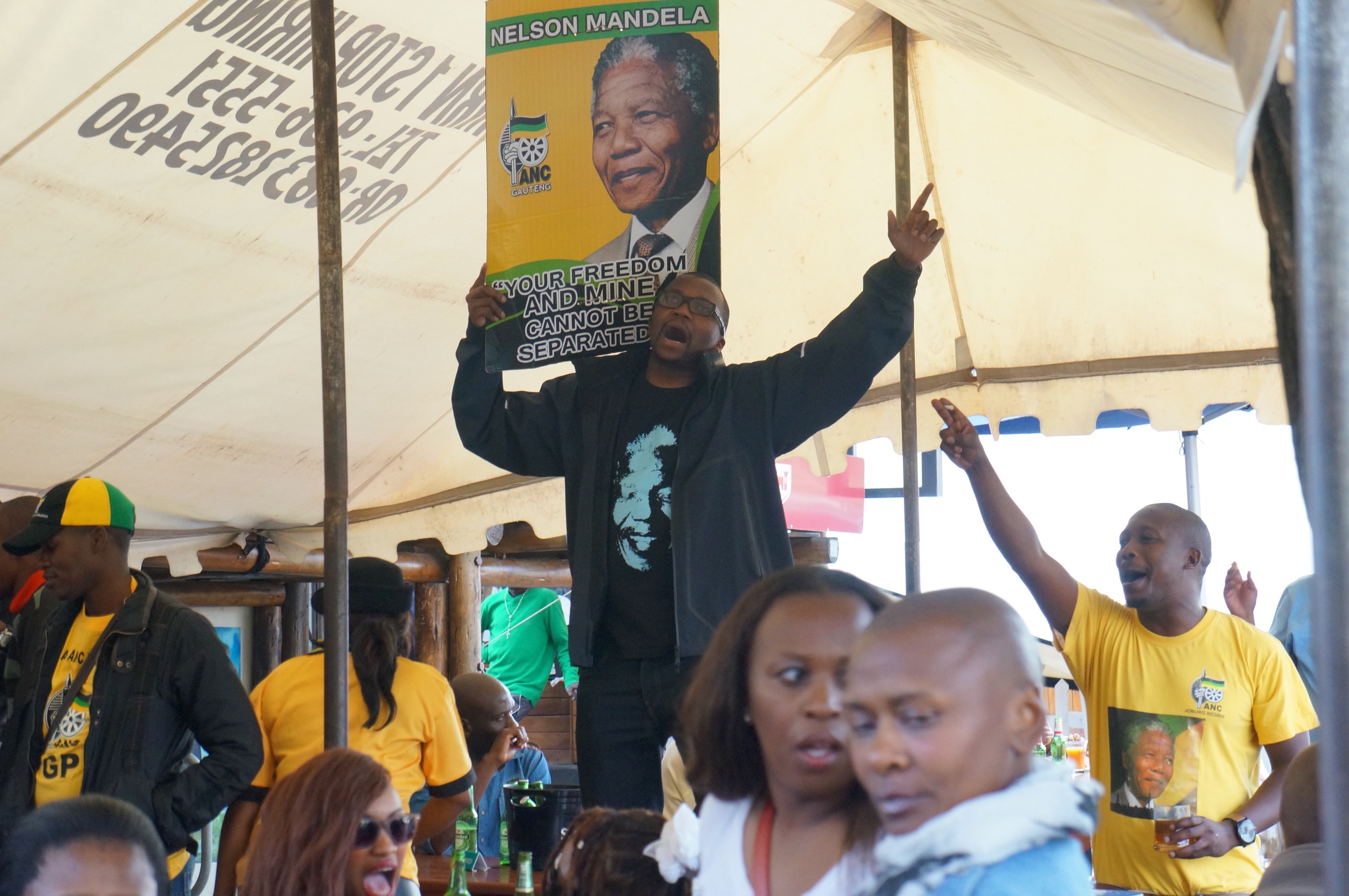

Soweto, the day of Mandela's death

International Day at the American International School of Johannesburg. Hope, for a future of cheering.