Open Letter to Perfectionist Parents, South Africa

Dear fellow Perfectionist Parents:

I have a fear of failure. It is one of the reasons I didn’t think I ever wanted to be a mother. I knew I could never meet my own expectations in the paramount job called parenting, and besides, I like to be in control. The task sounded too big, the deck too stacked against me in making sure my kid turned out just how I dreamed, flawlessly reflecting me and my values.

All that said, my son just turned nine.

Many years ago, when I was still single and planning on never-parenting, I saw an acquaintance in the lobby of the theatre. She was a young, beautiful mother. Her son, about two years old, ran up to us with a flower. He handed it to her and said, “I love you.” Then he ran back to his dad.

She watched him go and said to me, “I get to be his mom.”

I get to be his mom.

I’ve turned this phrase over and over in my head in the years since this tiny moment. It is how I found peace in becoming a parent, how I still find it in the long collection of days called being one.

Her words stuck with me, and there’s a simple truth in them that people like me need to hear. Most parents say, “That’s my son,” or “I am his mom.” This difference in verb is significant. In her mind, her child was not a direct extension of her. Even when he did something sweet, she didn’t take credit. She simply enjoyed that she had the chance live alongside him in a special way. Even referring to a two-year-old, her verb choice implied that he was his whole own person. She didn’t look at him as if there were eighteen years to mold him out of clay, to then put on display to the world. She just got to be his mom, to help fill his life with aweseomeness and love in the time it took him to become the person he already was on the inside.

Enter my child. He seemed to be the lens through which the world now looked at me, the final dissertation I wrote to justify who I was. I inevitably put too much pressure on myself to make sure he turned out cool in the ways that I deemed cool. I gave him the look when I didn’t like what he was doing, and I worried. What if my kid grew to be all kinds of things I didn’t particularly like? What if he turned on me and just wanted to play video games or shoot people or say racist things? Would that not be all my fault?

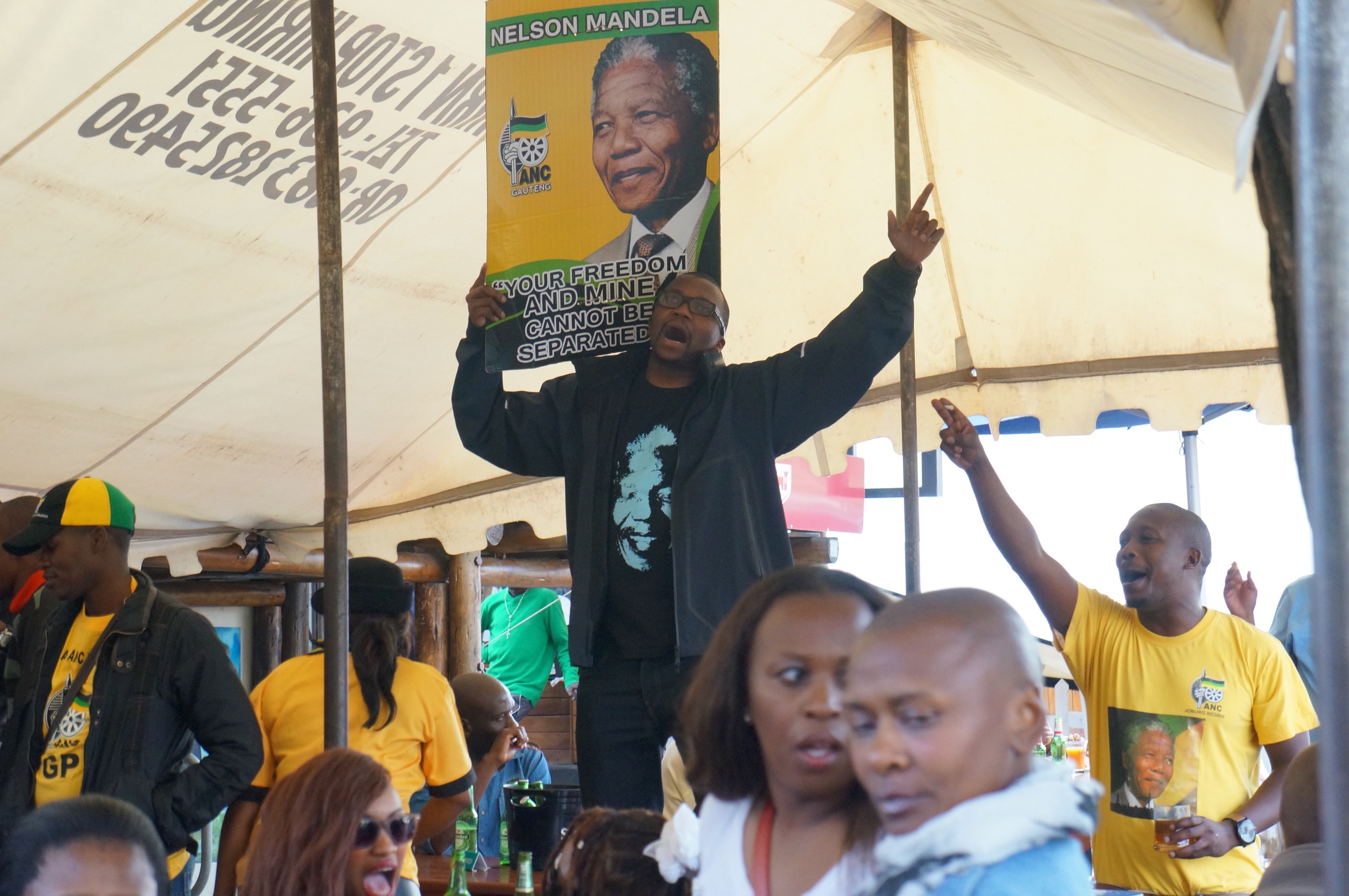

Photo by Jake Cross

In these early years as a mom I got another reminder. I had an Irish colleague named Joe, who was a great parent. When I’d ask Joe how his son was doing, he’d smile and say, “Ah, naughtier by the day.” (In an Irish accent. Just imagine.)

I found such comfort in the way Joe seemed totally fine with his kid being an imperfect, unpredictable person, not under a parent’s puppeteering control. Meanwhile, I was afraid some Parenting Gods were ever-grading me.

I’ve slowly come around to believe that kids are largely themselves from Day One. Whether the baby has colic, sensitive skin, hates being startled, loves hanging upside down, or sleeps better all swaddled up, parents can’t choose or control these things, right out of the gate. We can try to shape these characteristics, encourage or discourage all kinds of behaviors, but we are each born a whole being unto ourselves. Each step along the way, the tiny person (whose parent you get to be) is following his or her gut. Following some mysterious light clenched inside at the beginning of his or her world.

This borders on a nature versus nurture debate that we will probably never untangle. What I will say, given my tendency to want to be in control, is that it helps me, whether true or not, to lean back into the nature side a bit. It makes me a better parent to not think the entire future of my child is riding on my every motherly move.

Of course there are a million ways to help guide kids, teach them right from wrong, provide opportunities to help them find and thrive at things they love. The trick, for those like me, is to not hang my identity on each milestone they correctly pass, on each word they utter or hobby they choose. Sometimes I try to look at my child as this crazy person that came to live with me, instead of an audition piece I am setting out there in the world. Because when I let my perfectionist tendencies rule, I become a mother full of critiques. I am a mother full of disappointed looks. I am a mother I don’t want to be.

It is hard for me to not try and control who my kid is. I’m constantly learning to let go. As a perfectionist, what I need whispered in my ear, as often as possible, is “You get to be his mom.” Period.

Photo by Jake Cross

I aspire to be someone that could say that my kid is naughtier by the day and feel unjudged and confident that we’re all just doing our best. Everyone says that parents can’t do everything right, and the bummer is that this is so true. We can’t. Or maybe it’s not a bummer, maybe it is exactly what we perfectionists need in order to stretch ourselves in healthy ways. The best that we control freaks can do (and the hardest thing of all, for me) is to raise kids that are truly allowed to explore and be their own people, instead of a pressure-cooked new version of their parents.

I’m not exaggerating when I say that I have to remind myself every day to let go of the details. I try to hold my tongue about what he wants to wear or how he does his hair or what hangs on his backpack, or the annoying voices he uses, or the stupid plastic toys he wants to buy with his allowance. My kid is being himself. And when I think about it, that’s actually what I ultimately most want for him in this lifetime.

And me? It's not about me. I just get to be his mom.

Photo by Jake Cross

Photo by Jake Cross